The Design-Knowledge Framework

A Practical Guide to Prompting AI to Follow the Design Thinking Process

When I was a teenager, I loved to draw. I still love to draw, but back then it was all so new. I would come home from school and doodle on my drawing pad, whether it was a cartoon, a superhero, or an attempt at a real-life object. I became fascinated by the pursuit of the organization of lines. If the lines came together just right, then like magic, a face would appear out of thin air.

My exploration and passion for art led me to sign up for a summer-long life drawing course that, unbeknownst to me, would alter my perspective of the world for the rest of my life. Walking into the first day of class was surprising, as I was the youngest person in the class by far, which was less surprising when a model walked in derobed and posed on a platform in front of us. The teacher then walked up to the only light source currently on in the room, a fragile standing lamp and repositioned it toward the model. She then asked us to pick up our pieces of charcoal and not to outline the subject or try to draw them, but rather to focus only on creating the shapes of shadows that were stretching across their skin.

This hyper-focus on shadows alone and their importance in bringing our art to life had an outstanding effect on me. Never before had I been this aware of shadows and the impact they have on shaping the objects we see in real life. I felt newly awakened, and with each additional class in that course, my perspective on the world would break and reshape, allowing me to see it not only as an assembly of shadows but of contrasts, balance, patterns, proportions, and more. What I came to realize was that there was a set of principles, a framework, that humans have developed over time to help us perceive the world around us and apply it to the art we create.

Later in life, when I studied to become a visual designer, my perspective evolved further as I learned the principles of design. Then, later, it would continue to transform as I learned about design thinking, human-centered design, Don Norman’s design principles, Jacob Nielsen’s design heuristics, the Laws of UX, accessibility guidelines, cybernetics, strategic foresight, and so forth. Each time I learned a new principle or adopted another framework, my point of view on design was altered. So when I design a new component, screen, or experience, I am filtering the concept through a variety of lenses that help me arrive at the right solution.

Today, designers all over the world have access to a plethora of new tools powered by artificial intelligence. These range from conversational AI assistants to AI design-to-code tools. For the first time, designers have access to intelligent systems that can create based on prompts written in natural language. So, what’s the problem?

The problem

To understand the problem, I think it’s important to first understand how AI works and its current limitations.

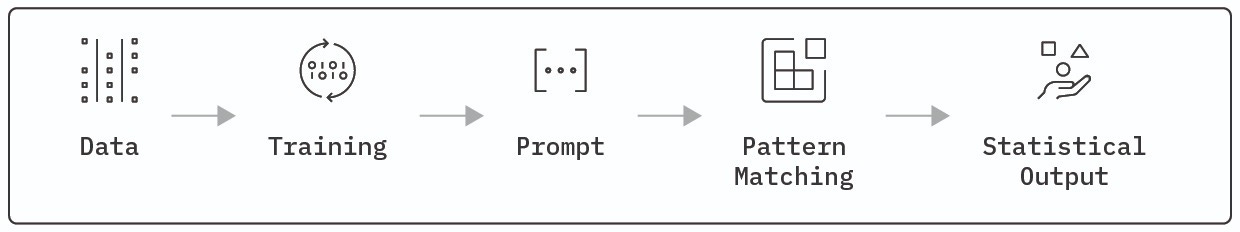

To build an AI model, you first need data, and you need a lot of it. These data sets range in size and variety, but they were intentionally sourced to obtain everything from photos of cats to the Broadway musical of Cats. The goal here is to get as much data as possible to fill in the potential gaps in knowledge.

The next thing you need to do is feed those data sets into your AI model to train it. The more data the model is given to train, the better it gets at understanding and utilizing that data to complete tasks. This part, in a way, is similar to how humans learn. Try to remember when you were first learning your multiplication table as a kid. The first time you saw the equation 2x2=?, you didn’t immediately know the answer, but the more you practiced your multiplication table, the quicker you were able to arrive at the answer that 2x2 = 4 or that 25x10 = 250.

This is when you, the designer, come in. You open up your favourite AI tool and you enter a prompt. Let’s say your prompt is ‘create a Date Picker component for an airline website’. Now, what happens is the AI tool will use all that data it was trained on to perform pattern matching based on your prompt. It will then use all the examples of Date Picker components it’s seen to arrive at a statistical output of the kind of Date Picker it should create to complete the task you prompted them with.

So if I asked for a Date Picker and it was able to deliver me a Date Picker, what’s the problem?

Well, remember when I walked through all of the frameworks, principles, and lenses I filter my concepts through? AI is not doing that. It’s not trying to understand the context of the user or how this component fits within the larger design system of the application. It’s just creating a Date Picker based on all the other versions it’s seen before. A good Designer isn’t just creating a component solely based on how other versions of the component look, but rather they are engaging in a complex critical thinking process to develop a solution that looks and functions well while also meeting the needs of users and the business.

Alright, so we have these AI-powered tools that can help us create things quickly, but they lack the ability to think like a human designer. How do we solve for this? One way is by priming the AI tool to follow a similar critical thinking process a designer would employ.

Prompt priming

Prompt priming is a method in which you split your prompt into two parts. Part 1 provides a clear set of instructions, guidelines, resources, and context needed to increase the likelihood that the AI is able to complete the task as directed. This frontloading helps the AI pattern-match against more relevant examples from its training data while also ensuring the output it develops is filtered through the variety of design principles and framework lenses before arriving at a final solution. We can consider this first part to be a contextual scaffolding that we are building for part 2 of the prompt, which is the request itself.

For the sake of clarity, moving forward, we will refer to Part 1 of the prompt as the Design-Knowledge Framework and Part 2 as the Design Request.

Design-knowledge framework

A successful design-knowledge framework is one that attempts to recreate the critical thinking process a designer would follow when given a design request to assist the AI in mimicking it. Essentially, we are laying down the tracks for the AI to follow to ensure that any concept it outputs first travels through a series of design gates made up of frameworks, guidelines, and principles.

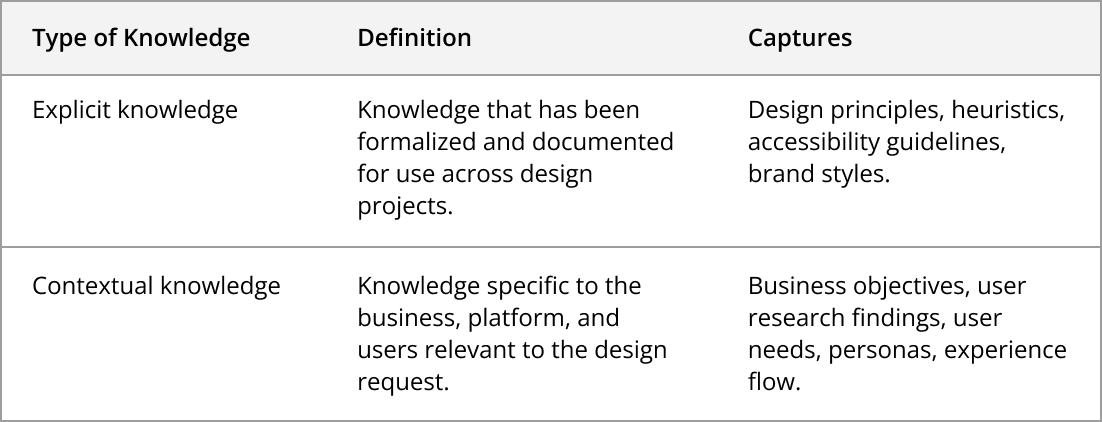

To build our design-knowledge framework, we must first divide design knowledge itself into two easily understood categories. These categories are explicit knowledge and contextual knowledge.

Utilizing these category concepts, design knowledge can then be organized into the Design-Knowledge Framework template below.

The template

You’re a senior UX designer assigned to design UI components and/or screens. This prompt is divided into two parts that guide you through a designer’s critical thinking process before generating your solution. Do not skip any step.

Part 1: Design-Knowledge Framework (Explicit + Contextual Knowledge)

Part 2: Design Request

Output Requirements:

Address all requirements outlined in this prompt

Include clear justification for design decisions, citing which framework principles were applied and why

If critical information is missing, ask clarifying questions before proceeding rather than making assumptions

Note any opportunities beyond stated requirements separately as recommendations

1. Explicit Knowledge

1.1 Frameworks, Methods, and Principles

The following foundational UX frameworks, methods, and principles must be considered and applied when applicable:

1.2 Accessibility

The design must comply with:

[For Designer: Specify accessibility requirements, e.g., WCAG 2.0 Level AA]

2. Contextual Knowledge

2.1 Objectives

Business: [For Designer: State the business objective]

User: [For Designer: State the user objective]

2.2 Persona

[For Designer: Describe primary user persona—key behaviors, needs, pain points]

2.3 Acceptance Criteria

[For Designer: List what must be included in the design]

2.4 Contextual Flow

[For Designer: Describe how this fits within the larger user journey or system]

2.5 Examples/References

[For Designer: Describe or provide URLs to reference examples]

2.6 Constraints

Technical: [For Designer: Any technical limitations]

Brand/Visual: [For Designer: Design system or brand guidelines to follow]

3. Design Request

[For Designer: Describe what needs to be designed, why it’s needed, and the desired output format (wireframe, description, annotated mockup, etc.)]

In practice

I used two AI tools (Claude and Figma Make) to test the Design-Knowledge Framework. For each AI tool, I ran the test twice, first by inputting the design request prompt without priming, and then I provided the design request with priming. The results were both interesting and surprising.

The immediate difference between the two approaches was during the reasoning stage. Without priming, the AI simply began to work on the design with very little transparency into its thought process. Claude’s reasoning simply stated, “I’ll create a polished train booking card component with an upgrade option. This will show the key booking details and make the upgrade path clear and appealing.” Whereas Figma said something similar, “I’ll create a train booking card component for a trip review page that displays the booking details and includes an upgrade option to business class. Let me build this with a clean, professional design.” Both tools followed those statements with a short description of some of the features and elements that went into the design.

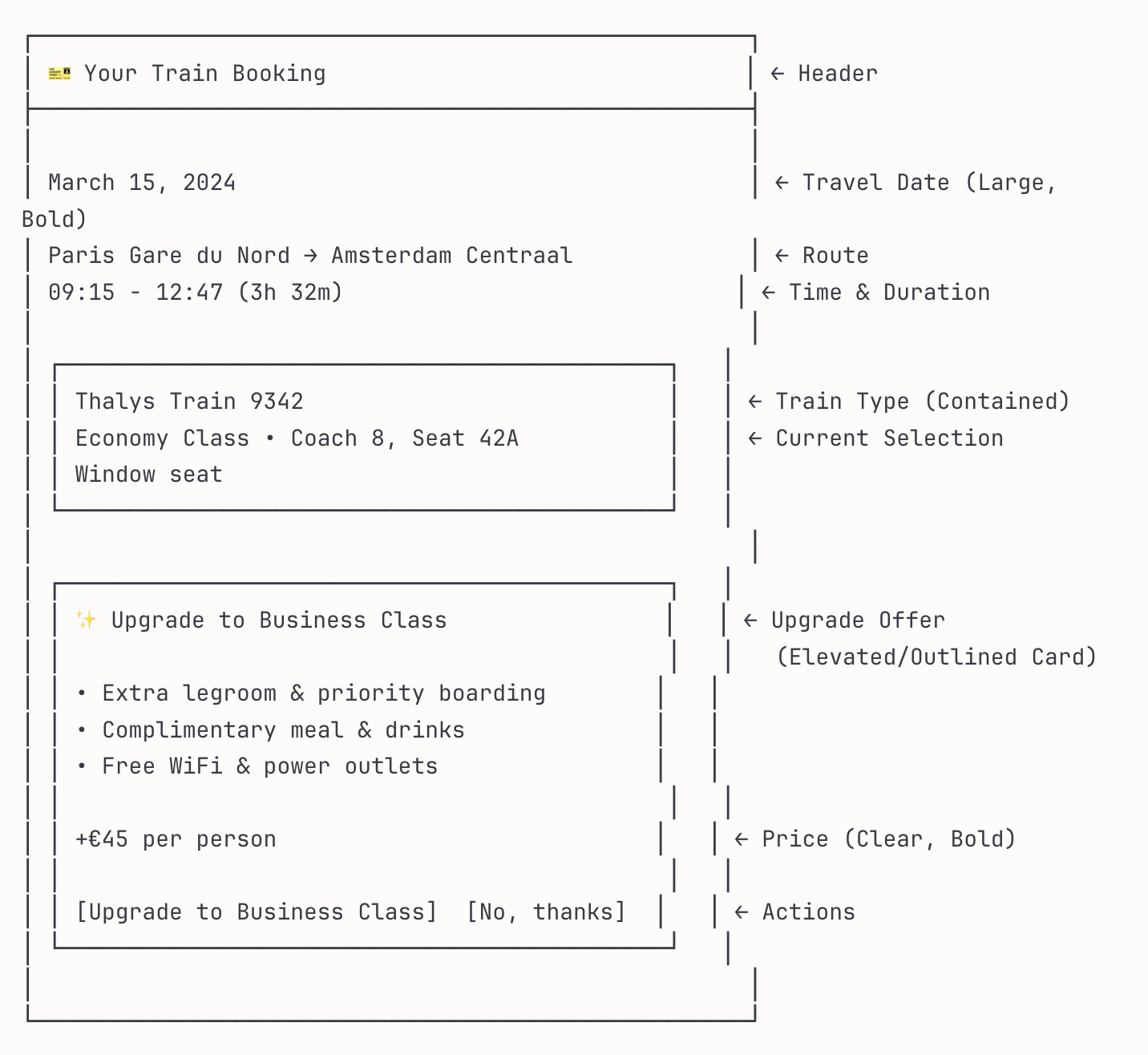

After being primed with the Design-Knowledge Framework, Claude first asked a few clarifying questions that were very similar to the types of questions a designer would ask when first receiving a design request. These included questions asking whether the pricing should be displayed, what the benefits of the upgrade were, and whether the user would have an opportunity to upgrade later in the flow if they declined at this time. After I answered those questions, Claude began to articulate its reasoning by walking through its critical thinking process in detail in a full report titled Design Analysis & Solution.

This reasoning report showed how the tool thought through each stage of the template, even creating a low-fidelity version of the concept layout with annotations. Additionally, the tool walked through which design principles or accessibility guidelines were relevant for the design it developed.

Figma’s reasoning was quite similar to Claude’s when primed with the Design-Knowledge Framework. It didn’t include a low-fidelity version, but did provide an even more granular walkthrough of principles and accessibility guidelines that it used to achieve the solution.

Additionally, when Claude and Figma were primed, they both included a set of recommendations beyond what was asked in the design request that ranged from design considerations or opportunities for testing and monitoring the success of the designs from a user and business perspective.

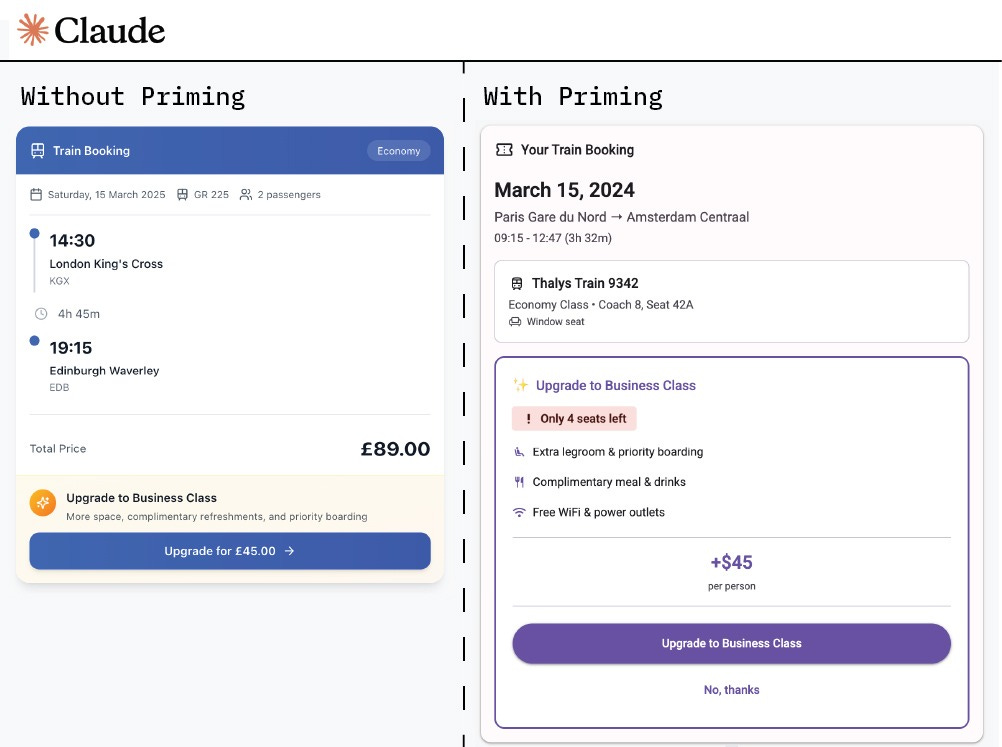

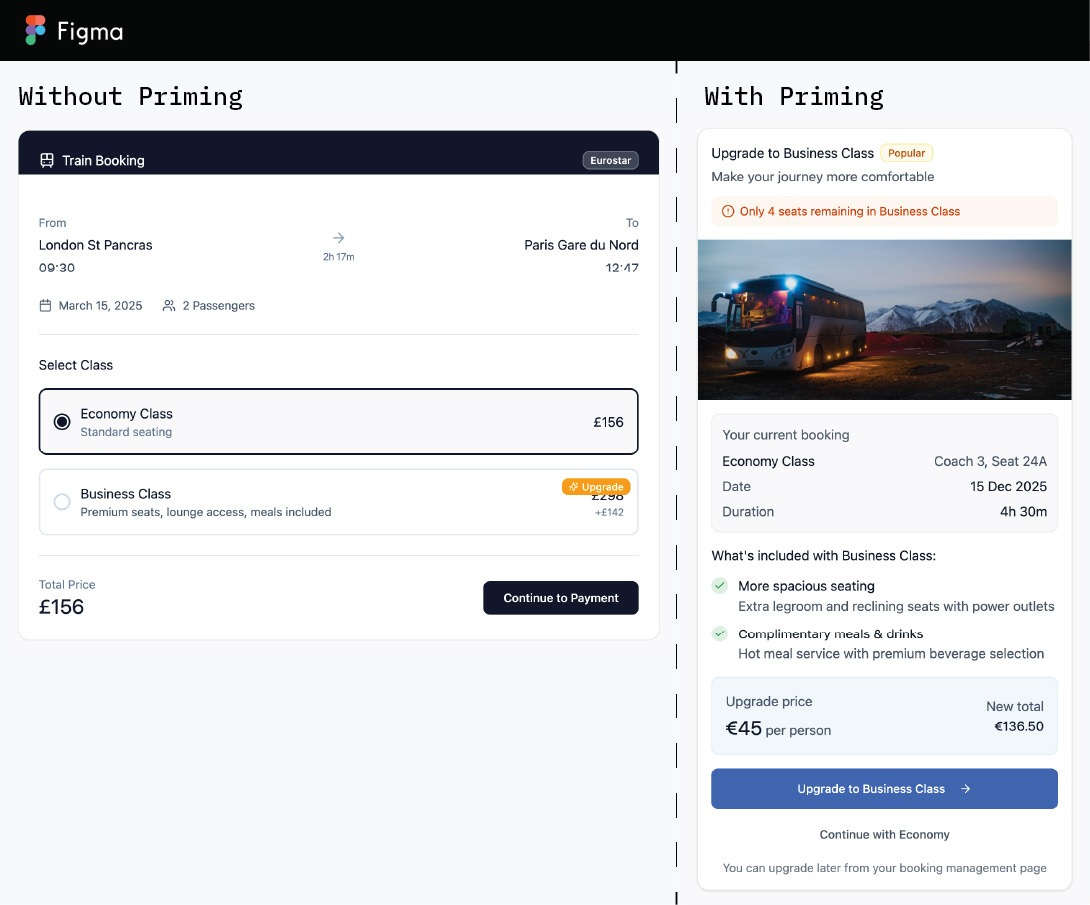

The final designs that both Claude and Figma developed during one of the tests are below, without and with priming:

Looking at the designs that were created by the AI tools without and with priming, a few distinctions can be made. Without priming, the designs that were developed were a lot more general. At first glance, they may look like a decent attempt, but on closer inspection, it is clear that they just built something that looks like examples from its training data without really trying to solve the problem. It lacks both business and user lenses.

Whereas the versions created by both tools using the Design-Knowledge Framework were more nuanced. The primed versions are more thought-out and are attempting to present a user-friendly design while also trying to increase the likelihood that users will upgrade. It doesn’t look like a component that was just slapped together, but was built through thoughtful design. One interesting mistake was that Figma Make seemed to have forgotten it was meant to be creating this component for train travel and ended up making it for buses in the primed version.

Where we go from here

The Design-Knowledge Framework was successful in guiding the AI tools to follow the critical thinking process of a designer, to the best of its ability. There was a clear difference between how the tools approached the design request, including whether it tried to clarify any questions, how it communicated its design process, the designs it developed, and the additional recommendations it provided.

Neither version of the final design, with or without priming, would be something I would consider ready for production. Even with priming, the design it created would need additional work by a designer to be finalized, and that’s an important point to understand from this explorative research. The Design-Knowledge Framework isn’t something that I created to assist in the replacement of designers, but rather it should illustrate just how complex and nuanced the design process is and all the existing knowledge that goes into it. No AI tool, any time soon, will be able to fully think like a designer. Like all creative professions, design is an articulation of life, personal experiences, and the understanding of human nature. These things are unique to humans, and in my opinion, always will be.

The Design-Knowledge Framework, I hope, will instead empower designers to use these tools more effectively during the early stages of design to speed the discovery and exploration phases, enabling designers to focus on the final designs, design strategy, and the overall user experience.